【简译】丁香、肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻皮的早期历史

The spices clove, nutmeg, and mace originated on only a handful of tiny islands in the Indonesian archipelago but came to have a dramatic, far-reaching impact on world trade. In antiquity, they became popular in the medicines of India and China, and they were a major component of European cuisine in the medieval period. European countries fought mightily for control of the spice trade.

丁香、肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻花起源于印度尼西亚群岛中的少数几个小岛,但它们对世界贸易产生了巨大、深远的影响。在古代,这些香料在印度和中国的药物中很受欢迎;在中世纪时期,它们是欧洲菜肴的主要组成部分。欧洲国家为控制香料贸易进行了激烈的竞争。

丁香、肉豆蔻种子与肉豆蔻皮(花)

The name clove refers to the dried, unopened buds of the evergreen tree, Syzygium caryophyllata in the myrtle family. Cloves were native to only five tiny, volcanic islands in the East Indian Archipelago: Ternate, Matir, Tidore, Makian, and Bacan, all belonging to the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas.

“丁香”这个名字是指桃金娘科常绿树丁香属的干燥、未开的花蕾。丁香原产于东印度群岛的五个小火山岛。Ternate(特尔纳特岛,又译德那第)、Matir、Tidore(蒂多尔)、Makian(马基安岛)和Bacan(巴干群岛),都属于马鲁古群岛(又译摩鹿加群岛)。

The nutmegs are the dark reddish-brown seeds within the fruits of Myristica fragrans, of the Myristicaceae family. These seeds are surrounded by a deep red, fleshy net-like membrane, or aril, which is the mace. The nutmeg tree was native to sheltered valleys on the hot, tropical Banda Islands in the Maluku region of Indonesia.

nutmeg是肉豆蔻科植物肉豆蔻肉果的深红棕色种子。这些种子被一层深红色、肉质的网状膜或假种皮所包围,这就是mace(肉豆蔻皮/花)。肉豆蔻树原产于印度尼西亚摩鹿加地区炎热的热带班达群岛的隐蔽山谷中。

丁香在古代的地位

The first mention of clove is in the Chinese literature of the Han period, around the 3rd century BCE. The spice called hi-sho-hiang ("bird’s tongue") was first used as a breath freshener; officers of the court were required to place cloves in their mouth before discussions with their sovereign. Cloves were used much more widely in medicines than food preparation. They were considered an internal warming herb, which helped dispel cold and warm the body. They were used as tonics and stimulants and were prescribed as a digestive aid and antiseptic. Cloves were used to treat a wide range of ailments including intestinal distress, impotence, diarrhea, vomiting, and cholera. They were made into a poultice to treat cracked nipples, scorpion stings, toothaches, and pretty much any abscess that caused pain.

大约在公元前3世纪,中国汉代的文献第一次提到了丁香。这种被称为hi-sho-hiang("鸟舌")的香料最早被用作口气清新剂;宫廷官员在与君主讨论之前必须将丁香放入口中。丁香在药物中的应用比在食物中的应用要广泛得多。它们被认为是一种热性草药,有助于驱散寒冷和温暖身体。它们被用作补药和兴奋剂,并被作为消化辅助剂和防腐剂处方。丁香还可以用来治疗广泛的疾病,包括肠道不适、阳痿、腹泻、呕吐和霍乱。人们用丁香制成膏药,用于治疗乳头破裂、蝎子蛰伤、牙痛和几乎所有引起疼痛的脓肿。

Cloves also played an important role in ancient Indian society, although they arrived there several centuries later than in China. Cloves became popular in traditional Ayurvedic medicine and were used to treat a wide range of problems including colds, asthma, indigestion, vomiting, toothache, laryngitis, low blood pressure, and impotence. In the ancient Sanskrit text, Charaka Saṃhita (1st century CE), it is stated that "one who wants clean, fresh, fragrant breath must keep nutmegs and cloves in the mouth" (Dalby, 50).

丁香在古代印度社会中也扮演着重要角色,尽管它们比中国晚了几个世纪到达那里。丁香在传统的阿育吠陀医学中很受欢迎,被用来治疗各种问题,包括感冒、哮喘、消化不良、呕吐、牙痛、喉炎、低血压和阳痿。在古老的梵文文献《Charaka Saṃhita》(公元1世纪)中指出,"想要干净、新鲜、芬芳的口气的人必须在口中保留肉豆蔻和丁香"(Dalby,50)。

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) was the first to describe cloves in the West in his Natural History (70 CE) where he recorded that "there is also in India a grain resembling that of pepper but larger and more fragile, called caryophyllom, which is reported to grow on the Indian lotus tree; it is imported here for the sake of its aroma". Roman emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306-337 CE) is said to have presented Saint Silvester, the bishop of Rome (314-335 CE), with gold and silver vessels filled with incense and spices, including 150 pounds (68 kg) of cloves. The Greek physician Paul of Aegina wrote in the 5th century CE: "It is of the nature of a flower of some tree, woody, black, almost as thick as a finger; reputed aromatic, sour, bitterish, hot and dry in the third degree; excellent in relishes and other prescriptions" (Dalby, 50). In his 6th-century CE Twelve Books on Medicine, the eminent Byzantine physician Alexander of Tralles recommended cloves for seasickness, gout, and appetite stimulation.

罗马作家老普林尼(公元23-79年)在他的《自然史》(公元70年)中首次描述了西方的丁香,他记录说:"在印度也有一种类似于胡椒的谷物,但更大更脆弱,叫做康乃馨(香石竹),据说它生长在印度的莲花树上;人们进口它是为了它的香气。" 据说罗马皇帝君士坦丁大帝(公元306-337年)向罗马主教圣西尔维斯特(公元314-335年)赠送了装满香和香料的金银器皿,包括150磅(68公斤)的丁香。希腊医生埃吉纳(Aegina)的保罗(Paul)(保卢斯·阿金塔)在公元5世纪写道:"它的性质是某种树的花,木质,黑色,几乎和手指一样粗;它是芳香的,酸的,苦的,热的,三度干;在调味品和其他处方中非常好"(Dalby, 50)。在公元6世纪的《医学十二书》中,著名的拜占庭医生Alexander of Tralles(亚历山大·奥法·特拉勒斯)推荐丁香用于晕船、痛风和刺激食欲。

古代的肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻花(皮)

Nutmeg and mace are frequently mentioned in the oldest scriptures of Hinduism in India, the Vedas, composed between 1500 and 1000 BCE. Nutmeg was recommended for improved digestion and was prescribed for headache, neural problems, fevers from colds, bad breath, and digestive problems. Later Indian texts described nutmeg as an important medicine for cardiac complaints, consumption, asthma, toothaches, dysentery, flatulence, and rheumatism.

肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻皮在印度最古老的经文《吠陀》中经常被提及,该经文是在公元前1500年至1000年之间创作的。肉豆蔻被推荐用于改善消化系统,并用于治疗头痛、神经问题、感冒发烧、口臭和消化系统问题。后来的印度文献将肉豆蔻描述为治疗心脏病、肺病、哮喘、牙痛、痢疾、胀气和风湿的重要药物。

Nutmeg and mace’s arrival in China was much later than in India; the first reference of what could have been nutmeg does not appear until the 3rd century CE in Ji Han’s Nanfang Caomu Zhuang (Record of Southern Plants and Trees). In it, he mentions a fragrant spice that comes from a tree whose flowers are colored like a lotus. Nutmeg is not commonly mentioned in the Chinese literature until the 8th century when it is used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, abdominal pain and bloating, reduced appetite, and indigestion.

肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻花到达中国的时间比印度晚得多;直到公元3世纪,在嵇含的《南方草木状》(南方植物和树种记录)中才第一次提到可能是肉豆蔻的东西。他在书中提到了一种芳香的香料,它来自一种花色如莲花的树木。肉豆蔻在中国文献中不常被提及,到了8世纪,它被用来治疗腹泻、痢疾、腹痛和腹胀、食欲下降和消化不良。

Nutmeg and mace were largely unknown to the West until the 5h or 6th century CE. Pliny was the first to write about a tree he called comacum, which had a fragrant nut, but it is not certain if he was really referring to nutmeg. The 1st-century CE Greek physician Dioscorides also vaguely refers to a red bark of unknown origin called macir. The first clear references to nutmeg and mace are not found until the Byzantine medical texts of the 6th century, which refer to a red bark, macis (mace), and a musky nut, nux muscata (nutmeg).

肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻花在很大程度上不为西方所知,直到公元5世纪或6世纪。普林尼是第一个写到一种他称之为comacum树的人,这种树的坚果很香,但不能确定它是否真的指的是肉豆蔻。公元1世纪的希腊医生Dioscorides也含糊地提到了一种叫做macir的红色树皮,其来源不明。直到6世纪的拜占庭医学文献才首次明确提到肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻皮(花),其中提到了一种红色树皮macis(肉豆蔻皮)和一种麝香型坚果nux muscata(肉豆蔻种子)。

阿拉伯医学和美食中的肉豆蔻种子、肉豆蔻花和丁香

The study of medicine was a major focus of Islamic scholars. During the 9th century and into the 10th, Harun al-Rashid of the Abbasid Caliphate and his son collected works of Greek medicine and other scientific texts from throughout the civilized world. These were taken to the Grand Library of Baghdad, the “House of Wisdom”, where the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegina, Hippocrates, and Dioscorides, were translated into Arabic. Based on their studies, Muslim physicians believed that sickness was the result of bodily imbalances, and these imbalances could be restored if the diet consisted of the right balance of herbs and spices including nutmeg and clove. These spices played a prominent role in the 9th-century medical texts written by the famous Arab physician, Isaac ibn Amran. His works, written in Arabic and translated into Hebrew, Latin, and Spanish, became the foundation of the medical curriculum of medieval Europe.

医学研究是伊斯兰学者的主要焦点之一。在9世纪和10世纪,阿拔斯王朝哈里发的哈伦·拉希德和他的儿子从整个文明世界收集希腊医学作品和其他科学文献。这些作品被带到巴格达的大图书馆,即 "智慧之家"。在那里,所有的希腊医学文献,包括盖伦、奥芮培锡阿斯、保卢斯·阿金塔、希波克拉底和迪奥斯科里德斯的所有作品,都被翻译成了阿拉伯语。根据研究,穆斯林医生认为,疾病是身体失衡的结果,如果饮食中包括正确平衡的草药和香料,如肉豆蔻和丁香,这些失衡是可以恢复的。这些香料在9世纪阿拉伯名医伊沙克·伊本·阿姆兰(Isaac ibn Amran)撰写的医学文献中发挥了突出作用。他的作品以阿拉伯语写成,并翻译成希伯来语、拉丁语和西班牙语,成为中世纪欧洲医学课程的基础。

The Arabs were the first to use cloves and nutmeg extensively in food preparation. In fact, spices were greatly appreciated all across the Middle East for their fragrance and medicinal properties, as well as for their enhancement of flavor in food. Herodotus, the ancient Greek writer, geographer, and historian, wrote in the 5th century BCE of the spices of Arabia that “the whole country is scented with them, and exhales an odor marvelously sweet” (The Histories, Book III). The Iraqi Ibn Sayyar al-Warrag listed cloves repeatedly in his 10th-century Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Cookery), the earliest known Arabic cookbook. In his highly regarded Al-Qanun fi al-Tib (The Canon of Medicine, 1025), Ibn Sina recommended “three-eighths of a dram of nutmeg with a small quantity of quince-juice” for “weakness of the stomach,” and he described nutmeg as a potent anesthetic concoction. Cloves and nutmeg played a dominant role in the popular, 13th-century Syrian cookbook Kitab al-Wuslah ila l-Habib and in an anonymous Andalusian cookbook.

阿拉伯人是第一个在食物制作中广泛使用丁香和肉豆蔻的人。事实上,在整个中东地区,香料因其香味和药用价值,以及对食物风味的提升而大受赞赏。古希腊作家、地理学家和历史学家希罗多德在公元前5世纪谈到阿拉伯的香料时写道:"整个国家都有香料的香味,并散发出令人惊叹的甜味"(《历史》第三册)。伊拉克人伊本·塞亚尔·瓦拉克(Ibn Sayyar al-Warrag)在其10世纪的Kitab al-Tabikh(《烹饪之书》)中多次提到丁香,这是已知的最早的阿拉伯烹饪书。伊本·西纳在其备受推崇的Al-Qanun fi al-Tib(《药典》,1025年)中建议用 "八分之三的肉豆蔻加少量榅桲汁 "治疗 "胃病",他还将肉豆蔻描述为一种有效的麻醉剂混合物。丁香和肉豆蔻在13世纪流行的叙利亚烹饪书《Kitab al-Wuslah ila l-Habib》和一本匿名的安达卢西亚烹饪书中发挥了主导作用。

欧洲烹饪中的肉豆蔻种子、肉豆蔻花和丁香

Before about the 12th century, medical practice in Europe was far behind the Muslims as there was little research being conducted, and because the medieval church considered disease a punishment from God, doctors could do little for their patients. It was not until new translations, observations, and methods of the Islamic world became available that western medicine began to move forward. Insights and methods from Islamic doctors brought many new advances to European medicine, including the widespread treatment of disease with spices.

大约在12世纪之前,欧洲的医疗实践远远落后于穆斯林,因为当时的研究很少,而且由于中世纪的教会认为疾病是上帝的惩罚,医生对病人几乎无能为力。直到有了伊斯兰世界的新译本、观察和方法,西方医学才开始向前发展。伊斯兰医生的见解和方法给欧洲医学带来了许多新的进步,包括广泛使用香料治疗疾病。

It is a bit hazy when nutmeg and cloves moved from the medicine cabinet into European cuisine, although their purported 'hot' and 'humid' properties were recommended for centuries in wintertime meals, according to the ancient teachings of Galen. In 716, the Frankish king Chilperic II is known to have granted the monks of Corbie Monastery a toll exception on their annual spice allotment of 30 pounds pepper, five of cinnamon, and two of cloves. There are records from the medieval monastery of St Gall in Switzerland that monks used cloves to season their fasting fish in the 9th century. In the 10th century, Andalusian traveler Ibrahim ibn Ya’qub noted that the burghers of Mainz (Germany) used cloves to season their food. When the king and queen of Scotland celebrated the Feast of the Assumption in 1256, their food was spiced with 50 pounds each of ginger, pepper, and cinnamon, 4 pounds of cloves, and 2 pounds each of nutmeg and mace. At the marriage of the Duke of Bavaria-Landshut in 1476, the banquets required 205 pounds of cinnamon, 286 pounds of ginger, and 85 pounds of nutmeg.

肉豆蔻和丁香是何时从药箱中进入欧洲菜肴的,这一点有些模糊,尽管根据盖伦的古老教义,它们所谓的 "热 "和 "湿 "特性在冬季饮食中被推荐了几个世纪。据了解,716年,法兰克国王希尔佩里克二世授予科尔比修道院的僧侣们每年30磅胡椒、5磅肉桂和2磅丁香的香料分配权,使他们可以例外收费。瑞士圣加尔中世纪修道院的记录显示,9世纪时,僧侣们用丁香来调味他们的斋菜鱼。10世纪,安达卢西亚旅行家易卜拉欣·伊本·雅库布(Ibrahim ibn Ya'qub)指出,美因茨(德国)的居民用丁香来调味。当苏格兰国王和王后在1256年庆祝圣母升天节时,他们的食物用生姜、胡椒和肉桂各50磅,丁香4磅,肉豆蔻和肉豆蔻各2磅来调味。在1476年巴伐利亚-兰茨胡特公爵的婚礼上,宴会消耗了205磅肉桂、286磅姜和85磅肉豆蔻。

Because of their distant supply lines, the spices were very costly in the Early and High Middle Ages, which restricted them to the wealthy and added greatly to their desirability. However, as the 11th and 12th centuries progressed, there was a steady rise in the popularity of Asian spices, stimulated by the Crusades and those who returned enchanted by the rich cuisine of Constantinople. The Venetians saw a window of opportunity and began to supply the European market with much greater quantities of spice. As Turner comments:

[By the late 12th century,] medieval cooks dreamed up hundreds of different applications, leaving practically no types of food without spice. There were rich and spicey sauces for meat and fish, based on an almost limitless number of combinations of cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, mace, pepper, and other spices, ground and mixed in with a host of locally grown herbs and aromatics. (105)

由于香料供应线遥远,香料在中世纪非常昂贵,这使它们只限于富人使用,并大大增加了香料的吸引力。然而,随着11世纪和12世纪的发展,在十字军东征和那些被君士坦丁堡丰富美食所吸引的人们的刺激下,亚洲香料的受欢迎程度稳步上升。威尼斯人看到了一个致富机会之窗,开始向欧洲市场供应数量更多的香料。正如特纳所评论的那样:

[到12世纪末],中世纪的厨师们想出了数百种不同的香料应用,几乎没有一种菜谱是不包含香料的。在丁香、肉豆蔻、肉桂、肉豆蔻皮、胡椒和其他香料无限组合的基础上,有丰富和辛辣的肉类和鱼类酱汁,研磨后与当地种植的大量草药和芳香剂混合在一起。(105)

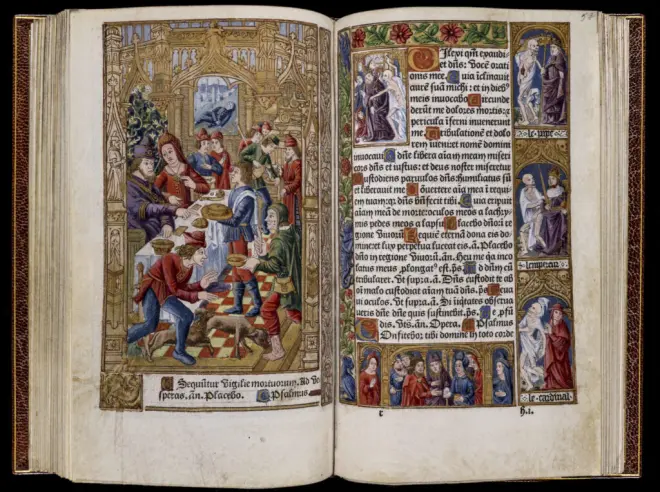

The popularity of spices in both cuisine and medicine reached its historical peak during the late Middle Ages in Europe. Food in medieval households was highly processed and richly spiced. Uncooked food was rarely eaten, even vegetables and fruit. The spices were used to season all types of food including meat, fish, soups, sweet dishes, and wine. It even became popular in medieval banquets to pass around a spice platter from which guests could choose extra seasonings for their already richly accented meals. The noted expert on medieval gastronomy, Paul Freedman, tells us that "spices were omnipresent in medieval gastronomy" and "something on the order of 75% of medieval recipes involves spices" (50).

香料在烹饪和医药方面的普及在欧洲中世纪晚期达到了历史的高峰。中世纪家庭的食物是高度加工的,并参有丰富的香料。人们很少吃未煮熟的食物,甚至蔬菜和水果也不例外。香料被用来调味所有类型的食物,包括肉、鱼、汤、甜菜和酒。在中世纪的宴会上,甚至还流行传阅香料拼盘,客人们可以从中选择额外的调味品,以满足他们本已经很丰富的膳食。著名的中世纪美食专家保罗·弗里德曼告诉我们,"香料在中世纪美食中无处不在","大约有75%的中世纪食谱涉及香料"(50)。

早期的肉豆蔻种子、肉豆蔻花和丁香贸易

Long before nutmeg, mace, and cloves became important to the outside world’s palates and medicines, there was vigorous interisland trade among the Spice Islands and the outer islands of Halmahera, Seram, Kei, and Aru. This trade was centered on the sago palm (Metroxylon sagu), which was the primary food source of the small, volcanic Maluku and Banda Islands, where little else grew but coconut and spices. The Bandanese became the undisputed leaders of the interisland trade of sago for spices, traveling in fleets of kora-kora canoes, propelled by rowers on platforms of bamboo lashed five feet away on either side of the canoe proper.

早在肉豆蔻、肉豆蔻皮和丁香对外部世界的口味和药物变得重要之前,香料群岛和哈尔马赫拉(贾伊洛洛)、塞兰岛、卡伊群岛和阿鲁群岛等外岛之间就存在着活跃的岛际贸易。这种贸易的中心是西米(Metroxylon sagu),它是马鲁古岛和班达岛这些小火山岛民的主要食物来源,那里除了椰子和香料外几乎没有其他植物生长。班达人成为岛际间以西谷椰子换取香料贸易的无可争议的领导者,他们乘坐科拉科拉独木舟船,由划手在独木舟两侧五英尺外的竹制平台上推动。

The sago palm was the staple food of hundreds of thousands of people, but it received little attention from the outside world until 1869, when the great Victorian naturalist and Darwin’s contemporary, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), described its characteristics at length in his epic The Malay Archipelago. About its taste, Wallace wrote:

The hot cakes are very nice with butter, and when made with the addition of a little sugar and grated cocoa-nut are quite a delicacy. They are soft, and something like corn-flour cakes, but have a slight characteristic flavor which is lost in the refined sago we use in this country …. They were my daily substitute for bread with my coffee. (van Wyhe, 514)

西米是数十万人的主食,但它很少受到外界的关注,直到1869年,伟大的维多利亚时代的自然学家和达尔文的同代人阿尔弗雷德·拉塞尔·华莱士(1823-1913)在其作品《马来群岛》中详细描述了它的特点。关于它的味道,华莱士写道:

热的蛋糕与黄油一起吃非常好,如果再加上一点糖和磨碎的可可果仁,那就相当美味了。它们很软,有点像玉米面的蛋糕,但有一点特有的味道,我们在这个国家使用的精制西米就没有这种味道....。它们是我每天喝咖啡时的面包替代品。(van Wyhe, 514)

Even with this heavy internal trading of spice for sago palm, the source of nutmeg and clove remained a mystery to the outside world for almost a millennium. Even the Arabians and Indians who sailed all across the Indian Ocean were long clueless about their origin. In the year 1000, the Arabic writer Ibrahim Ibn Wasif-Shah in his Summary of Marvels made this fanciful description about cloves and its source:

… somewhere near India is the island containing the Valley of Cloves. No merchants or sailors have ever been to the valley or have ever seen the kind of tree that produces cloves: its fruit they say is sold by genies. The sailors arrive at the island, place their items of merchandise on the shore, and return to their ship. Next morning, they find, beside each item, a quantity of cloves.

One man claimed to have begun to explore the island. He saw people who were yellow in color, beardless, dressed like women, with long hair, but they hid as he came near. After waiting a little, the merchants came back to the shore where they had left their merchandise, but this time they found no cloves, and they realized that this had happened because of the man who had seen the islanders. After some years absence, the merchants tried again and were able to revert back to the original system of trading.

The cloves are said to be pleasant to the taste when they are fresh. The islanders feed on them, and they never fall ill or grow old. It is also said that they dress in the leaves of a tree that grows only on that island and is unknown to other people. (Dalby, 50-51)

即使在这种大量的内部香料交易中,肉豆蔻和丁香的来源对外部世界来说仍然是个谜,几乎有一千年之久。即使是航行在印度洋各地的阿拉伯人和印度人也对它们的来源长期没有头绪。在1000年,阿拉伯作家Ibrahim Ibn Wasif-Shah在他的《奇迹摘要》中对丁香和它的来源做了这样的幻想描述。

......在印度附近的某个地方有一个包含丁香谷的岛屿。没有商人或水手去过这个山谷,也没有人见过生产丁香的那种树:他们说它的果实是由精灵出售的。水手们到达该岛,把他们的商品放在岸边,然后回到他们的船上。第二天早上,他们发现在每件商品旁边都有一定数量的丁香。

有一个人声称已经开始探索该岛。他看到一些人是黄色的,没有胡子,穿得像女人,有长头发,但当他走近时,他们就躲起来了。等了一会儿,商人们又回到了他们留下货物的岸边,但这次他们没有发现丁香,他们意识到这是因为那个看到岛民的人而发生的。在离开几年后,商人们再次尝试,并能恢复到原来的贸易体系。

据说,丁香在新鲜时味道很好。岛民们以丁香为食,他们从不生病或变老。还有人说,他们用一种只生长在该岛的树叶穿衣,其他民族不知道。(达尔比,50-51)

The entry of the nutmeg and cloves into world trade was long dependent on Malay and Indonesian sailors, with the Javanese being the primary players. As the 1st century CE dawned, three separate trading spheres were operating in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea:

Sailors from India and Sri Lanka were traveling to and from Bali, Java, and Sumatra across the Bay of Bengal.

Indonesian seafarers were conducting trade within the center of the vast archipelago itself.

Indonesians reached out into Southeast Asia and China.

肉豆蔻和丁香进入世界贸易,长期以来依赖于马来和印度尼西亚的水手,其中爪哇人是主要参与者。随着公元1世纪的到来,在印度洋和中国南海有三个独立的贸易圈在运作:

来自印度和斯里兰卡的水手穿越孟加拉湾,来往于巴厘岛、爪哇岛和苏门答腊岛。

印度尼西亚的海员在这个巨大的群岛中心进行贸易。

印度尼西亚人将触角伸向东南亚和中国。

Trade emporiums arose in Java and Sumatra, where Indian and later Arabian sailors could access all the spices and commodities of Southeast Asia and distribute them across the Indian Ocean. The Indian and Arabian ships typically sailed only as far east as the Strait of Malacca, and Indonesian ships made the other two journeys to eastern Indonesia and China. It was not until the High Middle Ages that Arabian and Indian sailors themselves knew the true home of the spices, clove, nutmeg, and mace.

爪哇岛和苏门答腊岛出现了贸易帝国,印度和后来的阿拉伯水手可以在那里获得东南亚的所有香料和商品,并将它们分销到印度洋沿岸。印度和阿拉伯的船只通常只向东航行到马六甲海峡,而印度尼西亚的船只则进行另外两次航行,前往印度尼西亚东部和中国。直到中世纪晚期,阿拉伯和印度水手自己才知道香料、丁香、肉豆蔻种子和肉豆蔻皮(花)的真正归宿。

参考书目:

Anonymous. The Annotated Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russel Wallace.. NUS Press, 2021.

Arndt, A. . "The flavors of Arabia ." Saudi Aramco World, 39/ 1988.

Dalby, Andrew. Dangerous Tastes. British Museum Press, 2000.

Ellen, R.F. "Sago subsistence and the trade in spices: a provisional model of ecological succession and imbalance in Moluccan history." Social and Ecological Systems, edited by Burnham, P.C. and Ellen, R.F . Academic Press, New York, 1979, 43–74.

Martinelli, Candida. The Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.

Pak, R. . "China and the trade in cloves, circa 960–1435." Journal of the American Oriental Society, 113/ 1993, pp. 1-13.

Perry, Charles & Roden, Claudia. Scents and Flavors. NYU Press, 2020.

Rosengarten, F. The Book of Spices. Pyramid Books, 1969.

Spice Migrations: ClovesAccessed 7 Oct 2021.

Turner, Jack. Spice. Vintage, 2005.

Weil, A.T. . "Nutmeg as a narcotic." Economic Botany , 19/3/1965, pp. 194–217.

原文作者:James F. Hancock

James F. Hancock是一名自由撰稿人,密歇根州立大学的名誉教授。他特别关注的方向是作物进化和贸易史。他的书包括《香料、香味和丝绸》(CABI),以及《种植园作物》(Routledge)。

原文网址:https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1849/the-early-history-of-clove-nutmeg--mace/

拓展阅读: